Showing posts with label CAT_policy. Show all posts

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

New structural economics

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

6:13 AM

Does economic theory provide anything like a concrete set of reliable policies for creating sustained economic growth in a middle-income country? Some contemporary economists believe that it is possible to answer this question in the affirmative. However, I don't find this confidence justified.

One such economist is Justin Yifu Lin. Lin is a leading Chinese economist who served as chief economist to the World Bank in 2008-2012. So Lin has a deep level of knowledge of the experience of developing countries and their efforts to achieve sustained growth. He believes that the answer to the question posed above is "yes", and he lays out the central components of such a policy in a framework that he describes as the "new structural economics". His analysis is presented in New Structural Economics: A Framework for Rethinking Development and Policy. (The book is also available in PDF format from the World Bank directly; link.)

Lin's analysis is intended to be relevant for all low- and middle-income countries (e.g. Brazil, Nigeria, or Indonesia); but the primary application is China. So his question comes down to this: what steps does the Chinese state need to take to burst out of the "middle income trap" and bring per capita incomes in the country up to the level of high-income countries in the OECD?

So what are the core premises of Lin's analysis of sustainable economic growth? Two are most basic: the market should govern prices, and the state should make intelligent policies and investments that encourage the "right kind" of innovation in economic activity in the country. Here is an extended description of the core claims of the book:

Long-term sustainable and inclusive growth is the driving force for poverty reduction in developing countries, and for convergence with developed economies. The current global crisis, the most serious one since the Great Depression, calls for a rethinking of economic theories. It is therefore a good time for economists to reexamine development theories as well. This paper discusses the evolution of development thinking since the end of World War II and suggests a framework to enable developing countries to achieve sustainable growth, eliminate poverty, and narrow the income gap with the developed countries. The proposed framework, called a neoclassical approach to structure and change in the process of economic development, or new structural economics, is based on the following ideas:So a state needs to secure the conditions for well-functioning markets; and it needs to establish an industrial strategy that is guided by a careful empirical analysis of the country's comparative advantage in the global economic environment. In practice this seems to amount to the idea that the middle-income economy should identify the leading economies' declining industries and compete with those on the basis of labor costs and mid-level technology. Lin also emphasizes the important role of the state in making appropriate infrastructure investments to support the chosen industrial strategy. This is a "structural economic theory" because it is guided by the idea that a developing economy needs to incrementally achieve structural transformation from a given mix of agriculture, industry, and service to a successor mix, based on the resources held by the economy that give it advantage in a particular set of technologies and production techniques. Here is a representative statement:

First, an economy�s structure of factor endowments evolves from one level of development to another. Therefore, the industrial structure of a given economy will be different at different levels of development. Each industrial structure requires corresponding infrastructure (both tangible and intangible) to facilitate its operations and transactions.

Second, each level of economic development is a point along the continuum from a low-income agrarian economy to a high-income post-industrialized economy, not a dichotomy of two economic development levels (�poor� versus �rich� or �developing� versus �industrialized�). Industrial upgrading and infrastructure improvement targets in developing countries should not necessarily draw from those that exist in high-income countries.

Third, at each given level of development, the market is the basic mechanism for effective resource allocation. However, economic development as a dynamic process entails structural changes, involving industrial upgrading and corresponding improvements in �hard� (tangible) and �soft� (intangible) infrastructure at each level. Such upgrading and improvements require an inherent coordination, with large externalities to firms� transaction costs and returns to capital investment. Thus, in addition to an effective market mechanism, the government should play an active role in facilitating structural changes. (14-15)

Countries at different levels of development tend to have different economic structures due to differences in their endowments. Factor endowments for countries at the early levels of development are typically characterized by a relative scarcity of capital and relative abundance of labor or resources. Their production activities tend to be labor intensive or resource intensive (mostly in subsistence agriculture, animal husbandry, fishery, and the mining sector) and usually rely on conventional, mature technologies and produce �mature,� well-established products. Except for mining and plantations, their production has limited economies of scale. Their firm sizes are usually relatively small, with market transactions often informal, limited to local markets with familiar people. The hard and soft infrastructure required for facilitating that type of production and market transactions is limited and relatively simple and rudimentary. (22)Some common development strategies fail to conform to these ideas. So, for example, import substitution is a bad basis for economic development, because it subverts the market and it distorts the investment strategies of the state and the private sector; it fails to guide the given economy on a path pursuing incremental comparative advantage (18).

Even less does Lin's theory address the kinds of issues raised by "post-development" thinkers like Arturo Escobar in Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Escobar challenges some of the most basic assumptions of classical economic development theory, beginning with the idea that industry-lead structural transformation is the unique pathway to human flourishing in the less-developed world. Escobar's critique involves several ideas. First is the observation that economic development theory since 1945 has been Eurocentric and implicitly colonial, in that it depends upon exoticized representations of the industrialized North and the traditional agricultural South. Against this colonial representation of global development Escobar emphasizes the need for a more ethnographic and cultural understanding of development. Second, this Eurocentric view brings along with it some crucial distributive implications -- essentially, that the resources and labor of the developing world should continue to provide part of the surplus that supports the affluence of the North. Third, Escobar casts doubt on the value of development "experts" in the design of development strategies for poor countries in the South (46). Local knowledge is a crucial part of sound economic progress for countries like Nigeria, Brazil, or Indonesia; but the development profession seeks to replace local knowledge with expert opinion. So Escobar highlights local knowledge, the importance of culture, and the importance of self-determination in theory and policy as key ingredients of a sustainable plan for economic development in the countries of the post-colonial South.

Why do these alternative approaches to development theory matter? Why is the absence of a discussion of wellbeing, flourishing, or culture an important lacuna in New Structural Economics? Because it results in a view of economic development that lacks a compass. If we haven't given rigorous thought to what the goal of development is -- and Sen demonstrates that it is entirely possible to do that -- then we are guided only by a rote set of recommendations: increase productivity, increase efficiency, increase market penetration, increase per capita income. But the fact of substantial rise in economic inequalities through a growth process means that it is very possible that only a minority of citizens will be affected. And the fact that a typical family's income has risen by 50% may be less important than the availability of a nearby health clinic for their overall wellbeing. And both of these kinds of considerations seem to be relevant in the case of China. It is well documented that there has been a substantial increase in China's income (and wealth) inequalities in the past thirty years (link, link). And it is also reasonably clear that China's commitment to social security provisioning is far lower than that of OECD countries. So it is far from clear that China's recent history of growth has been proportionally successful in enhancing the quality of life and human flourishing of the mass of its population (link).

The unstated assumption is that countries that pursue these prescriptions -- "maintain efficient markets, adopt an industrial strategy that accurately tracks shifts in comparative advantage, support investment in appropriate infrastructure to reduce transaction costs" -- will have superior long-term growth in per capita income and will be better able to ensure enhancements in the quality of life of their citizens. But this is nothing more than naive confidence in "trickle-down" economics. It ignores completely the problem of the likelihood of rising economic inequalities, and it doesn't provide any detailed analysis of how quality of life and human flourishing are supposed to rise. Development economics without capabilities and wellbeing is inherently incomplete; worse, it is a bad guide to policy choices.

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

Thurgood Marshall's future

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

2:09 PM

Thurgood Marshall was awarded the Liberty Medal by the National Constitution Center in 1992 (link). Marshall had stepped down as a justice of the US Supreme Court as its first African-American justice. Prior to his distinguished service on the Supreme Court he was the lead lawyer in the 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. He was appointed by President Johnson in 1967 and retired from the Supreme Court in 1991. He was an astute and engaged observer concerning the state of race relations and racial discrimination in the United States.

The acceptance speech that he provided on the occasion of the Liberty Medal ceremony is deeply sobering in virtue of the observations Marshall made about the state of racial equality in America in 1992, twenty-four years ago. Here are a few lines from the speech:

I wish I could say that racism and prejudice were only distant memories....

Democracy just cannot flourish amid fear. Liberty cannot bloom amid hate. Justice cannot take root amid rage. America must get to work. In the chill climate in which we live, we must go against the prevailing wind....

We must dissent from the fear, the hatred and the mistrust.... We must dissent because America can do better, because America has no choice but to do better.In 2016 these observations seem equally timely, in ways that Marshall could not have anticipated. First, his observation that racism and prejudice persist remains true today in the United States (link). It doesn't take a social-science genius to recognize the realities of racial disparities in every important dimension of contemporary life -- income and property, health, education, occupation, quality of housing, or life satisfaction. And most of these disparities persist even controlling for factors like education levels. These disparities are the visible manifestation of the workings of racial discrimination.

The next paragraph of Marshall's speech is equally insightful. Several currents of political psychology are particularly toxic when it comes to improving the status of race relations in a democracy. A polity that embodies large portions of fear, hate, and rage is particularly challenged when it comes to building an inclusive polity founded on democratic values. Democracy requires a substantial degree of trust and mutual respect, if the identities and interests of various groups are to be fully incorporated. And yet democracy fundamentally requires inclusion and equality. So stoking hatred, suspicion, and fear is fundamentally anti-democratic.

Marshall closes with a theme that has almost always been key to the Civil Rights movement and the struggle for full racial equality and respect in our country: a basic optimism that the American public both needs and wants a polity that transcends the differences of race and religion that are a core part of our history and our future. We want a society that treats everyone equality and respectfully. And we reject political advocates who seek to undermine our collective commitments and civic values. "America can do better."

Why do we have "no choice" in this matter? Here we have to extrapolate, but my understanding of Marshall's meaning has to do with social stability, on multiple levels. A society divided into large groups of citizens who distrust, fear, and disrespect each other is surely a society that hangs at the edge of conflict. Conflict may take the form of group-on-group violence, as is seen periodically in India. Or it may take a more chaotic form, with isolated individual acts of violence against members of some groups, as we see in the US today through the rise in hate crimes against Muslims.

But there is another reason why we have no choice: because we fundamentally cherish the values and institutions of a pluralistic democracy, and because the politics of hate are ultimately inconsistent with those values and institutions. So if we value democracy, then we must struggle against the politics of hate and suspicion.

There are always political opportunities available to unscrupulous politicians in the rhetoric of division, mistrust, and hate. It is up to all of us to follow Marshall's lead and insist that our democracy depends upon equality and mutual respect. We must therefore work hard to maintain the integrity of the political values of equality and civil respect associated with our political tradition. "America has no choice but to do better."

Friday, July 29, 2016

Survey research on right-wing extremism in Europe

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

2:41 PM

European research and policy organizations have devoted a fair amount of attention to the rise of extremist movements and intolerance in European countries in the past ten years. Attention has been directed towards both aspects of the problem that have been mentioned in earlier posts -- rising public attitudes of intolerance, and the mobilization and spread of hate-based right-wing organizations. (The topic has also received a great deal of attention in the press -- for example, in the Guardian (link), the New York Times (link), and Spiegel (link).)

One useful report is Intolerance, Prejudice and Discrimination: A European Report (link), authored by Andreas Zick, Beate Kupper, and Andreas Hovermann (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2011). The study is based on survey research in eight countries (Germany, Britain, France, Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, Poland, and Hungary). Particularly interesting are the results on anti-semitism, anti-muslimism, and homophobia (56 ff.). Here are the opening paragraphs of the authors' foreword:

Intolerance threatens the social cohesion of plural and democratic societies. It reflects the extent to which we respect or reject social, ethnic, cultural and religious minorities. It marks out those who are �strange�, �other� or �out- siders�, who are not equal, less worthy. The most visible expression of intolerance and discrimination is prejudice. Indicators of intolerance such as prejudice, anti-democratic attitudes and the prevalence of discrimination consequently represent sensitive measures of social cohesion.And here are a few of their central findings, based on survey research in these eight countries:

Investigating intolerance, prejudice and discrimination is an important process of self-reflection for society and crucial to the protection of groups and minorities. We should also remember that intolerance towards one group is usually associated with negativity towards others. The European Union acknowledged this when it declared 1997 the European Year against Racism. In the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam the European Union called for joint efforts to combat prejudice and discrimination experienced by groups and individuals on the basis of their ethnic features, cultural background, religion, gender, sexual orientation, age or disability. (11)

Group-focused enmity is widespread in Europe. It is weakest in the Netherlands, and strongest in Poland and Hungary. With respect to anti-immigrant attitudes, anti-Muslim attitudes and racism there are only minor differences between the countries, while differences in the extent of anti-Semitism, sexism and homophobia are much more marked.

About half of all European respondents believe there are too many immi- grants in their country. Between 17 percent in the Netherlands and more than 70 percent in Poland believe that Jews seek to benefit from their forebears� suffering during the Nazi era. About one third of respondents believe there is a natural hierarchy of ethnicity. Half or more condemn Islam as �a religion of intolerance�. A majority in Europe also subscribe to sexist attitudes rooted in traditional gender roles and demand that: �Women should take their role as wives and mothers more seriously.� With a figure of about one third, Dutch respondents are least likely to affirm sexist attitudes. The proportion opposing equal rights for homosexuals ranges between 17 percent in the Netherlands and 88 percent in Poland; they believe it is not good �to allow marriages between two men or two women�. (13)These researchers find three underlying "ideological orientations" associated with these patterns of intolerance and discrimination: authoritarianism, "social dominance orientation", and the rejection of diversity. And the factors that work against intolerance include "trust in others, the ability to forge firm friendships, contact with immigrants, and above all a positive basic attitude towards diversity" (14).

The topic of the incidence of intolerance in European countries is also the subject of research in the Eurobarometer project. Here are two Eurobarometer reports from 2008 and 2012 that attempt to measure changes in levels of discrimination and prejudice (Discrimination in the European Union, 2008; link; 2012; link).

Also from the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung is the report Is Europe on the "Right" Path?: Right-wing extremism and right-wing populism in Europe (link). This report provides country studies of the radical right in Germany, France, Britain, Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. Here is how Britta Schellenberg undertakes to synthesize these wide-ranging findings:

Taken as a whole, the contributions in the present volume clearly illustrate the common features and differences within the radical right in Europe. Analyses of the current phenomenon of the various radical-right movements and a differentiated analysis of their origins are fundamental for considering counter-strategies. Obviously, there is no single, generally valid strategy that guarantees an optimal way of combating the radical right. In fact, strategies can be successful only if they match up to the specific political and social context and if the maximum possible number of players from politics, the legal system, the media, educational institutions and civil society are agreed upon them.Each country study is detailed and interesting. The France study focuses on the Front National and Jean-Marie Le Pen's success (and later Marine Le Pen's success) since the 1984 European election in gaining visible support and electoral success with 10% to 15% of the vote (84). The Mouvement pour la France (MPF) and its leader Philippe de Villiers also receive attention in the report. And the resurgence of skinheads and direct action neo-fascists like the "violence-prone street brawlers of the Groupe Union Defense" are discussed (89-90).

However, we can identify general requirements for strategies against right-wing extremism and xenophobia that form a framework broad enough to allow a European perspective. For concrete work in a particular place, this framework must be filled out with individual measures and activities specific to the situation and location. But for now, we shall now proceed to take a bird�s eye view and answer the basic questions as to what preconditions have to be created for maximum success in combating radical-right-wing attacks, parties and attitudes. (309)

The essay develops a handful of strategies for combatting right-wing movements:

- A comprehensive approach: Identifying and naming problems and strategically combating the radical right

- Political involvement: Confront, don�t cooperate

- Determining the focus: Protection against discrimination, and diversity and equality

- Allowing civil society to develop, and strengthening civic commitment

- Education for democracy and human rights

- The EU is being degraded into an enforcer of austerity measures across the continent. It is essential to restore the idea of the EU as a regional network of states that stand together in solidarity in order to promote mutual wellbeing, good living standards, tolerant societies, and democratic values that are shared by all.

- Furthermore it is vital to explain the local benefits of EU membership to ordinary people with a clear and understandable message.

- There need to be more efficient and accessible training and exchange programmes in order to decrease the distance between EU institutions and citizens.

- Diversity must be increased and a greater inclusiveness within EU institutions is required, with mechanisms to enable a much more accurate representation of the European population in EU institutions.

- Progressives should be strident in defending greater global and European integration against the often empty criticisms of right-wing populists and extremists.

- We recommend that different stakeholders collaborate with each other in a knowledge exchange in order to provide public officials with EU-wide training.

- Establishing quotas for those who are elected as candidates, by increasing leadership in minority groups, and via private-public partnerships to help promote equality in business as well as the public sector.

- Hate speech has to be monitored in the European Parliament by an independent body and the existing sanctions regarding hate speech need to be reviewed.

- Social media should be used in this effort to confront the advocacy of hatred and that a dialogue should be promoted between internet providers and social media companies, examining among others the possibility of creating a new platform for non-governmental organizations and the civil society. (5-6)

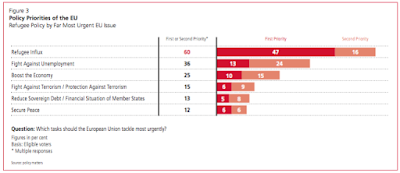

Here is a summary table based on results from all eight countries ranking the relative weight of EU priorities for EU citizens. Solving the refugee crisis dwarfs concern about other issues, though unemployment comes in as a substantial second.

Given Brexit, it is interesting to see the relative levels of dissatisfaction with EU membership in other countries as well. An average of 34% of respondents found that "disadvantages exceed advantages" in EU membership for their country, with the Czech Republic at 44% on this question and Spain at only 22%.

These are interesting survey results describing the growth of right-wing extremism in Europe. But these studies are limited in their explanatory reach. They are largely descriptive; they give a basis for assessing the dimensions of the problem in terms of population attitudes and right-wing extremist organizations. But there is little by the way of sociological analysis of the mechanisms through which these extremist attitudes and processes of activism proliferate and grow. In an upcoming post I will review some recent work on the ethnography of right-wing movements that will allow a somewhat deeper understanding of the dynamics of these movements.

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

Ideologies and organizations as causes of political extremism

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

4:31 AM

In a recent post I addressed the issue of the rise of mass intolerance and hate from the point of view of the public -- the processes through which sizable numbers of members of society come to be more intolerant in their attitudes and behaviors. This involves looking at the problem as being analogous to epidemiology -- the contagion through a population of the social psychology of hate and intolerance.

But this is only a part of the story. Right-wing political movements are fueled by ideologies and organizations, and when they come to power their success is at least partially attributable to these higher-level social factors. A movement can't succeed without gaining grassroots followers, to be sure. But it may be that the authoritarian and racist politics of a movement derive more from the higher-level factors of ideology and organization than the retail racism and social psychology of the populace.

This is the heart of the approach taken by Fritz Stern in The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in the Rise of the Germanic Ideology , where he gives a careful and detailed accounting of the philosophies and mental frameworks that underlay the progress of reactionary and racist parties in Germany (link). It is also the approach taken by Janek Wasserman in Black Vienna: The Radical Right in the Red City, 1918-1938, where the ideas of conservative religious dogmas, anti-semitism, and a hatred of modern secularism fueled the rise of Austrofascism. Wasserman gives little attention to the street-level politics of the struggles and mobilizations of left and right in Austria (unlike Arthur Koestler's gritty accounts of the mobilizations and street fighting of communists and fascists in Berlin; link).

, where he gives a careful and detailed accounting of the philosophies and mental frameworks that underlay the progress of reactionary and racist parties in Germany (link). It is also the approach taken by Janek Wasserman in Black Vienna: The Radical Right in the Red City, 1918-1938, where the ideas of conservative religious dogmas, anti-semitism, and a hatred of modern secularism fueled the rise of Austrofascism. Wasserman gives little attention to the street-level politics of the struggles and mobilizations of left and right in Austria (unlike Arthur Koestler's gritty accounts of the mobilizations and street fighting of communists and fascists in Berlin; link).

If we look at the problem from this point of view, then the rise of right-wing extremist movements needs to be analyzed in terms of the ideologies that lead them and the organizations through which they attempt to bring about their political ends. In the United States the ideology of the right has a number of leading values: religious fundamentalism, nativism, anti-government and anti-tax rhetoric, free market fundamentalism, suspicion, homophobia, and cultural conservativism. And these threads have been woven together into powerful and motivating narratives of American history and the political choices the country faces for tens of millions of Americans.

In this light the writings of Richard Hofstadter, discussed in an earlier post, are quite important. Hofstadter traces the specifics of a fairly distinctive conservative ideology in the United States, a worldview of society and politics that has persisted in the organs of public expression -- newspapers, activists, professors, clergy -- over a very long time. And these tropes in turn find expression in the activism and mobilization of extremist groups like the armed groups who took over the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge last winter. These ideological strands become currents of extremist values around which individual entrepreneurs organize their appeals to potential followers. (Many of these themes are finding expression on the convention stage in Cleveland this week.)

It is a very interesting question to consider how mass consciousness in a population maintains a "folk" political philosophy over generations. How have American nativism and mistrust of government been sustained in the populace since 1900? Why does anti-semitism persist so strongly in some European countries where the Holocaust left almost no Jewish residents at all? What are the mechanisms of transmission and reproduction that make this possible? To what extent is this an organic process of popular transmission, and to what extent is it the result of ongoing ideological struggles? It is clear that ideologies have institutional embodiments. And it is an important task for political sociology to map out the ways these institutions work. Obviously newspapers, media, religious centers, and universities play key roles in the transmission of political frameworks to new generations of citizens; and the influence of family traditions and daily discussions of current events play a crucial role in the transmission of values and frameworks as well.

The organizations of the right include a range of configurations of groups in civil society -- right-wing political parties, religious organizations, anti-government groups, and cause-based organizations (anti-gay marriage, pro-gun groups, business advocacy groups, conservative student organizations). The hate groups tracked by the SPLC are the extreme fringe of this world. These kinds of organizations do their best to frame political choices and antagonisms around their core ideological tropes, and they do everything possible to stir up the emotions and angers of their followers and potential followers around these values.

Ideologies and organizations are clearly intertwined. Organizations have purposive agendas; and one important mechanism for furthering their agendas is to influence the content and nature of prominent expressions of social worldviews. So funneling cash into right-leaning think tanks, enhancing the visibility and credibility of their spokesmen, and turning up the volume on extreme right-wing media outlets are all understandable strategies of ideological conflict. (Naomi Oreskes' and Eric Conway's important book Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming documents these strategies in the case of climate science; link.) But likewise, the currency of a bundle of ideological beliefs and values in a part of the population is a huge boost for the ability of an organization to finance itself, draw followers, and exercise influence.

So we can look at the rise of large social movements, including those based on hate and suspicion, from two complementary perspectives. We can consider the micro-level processes through which beliefs and activism spread through a population, and we can look at the higher-level factors of ideology and organization within which these political processes unfold. In reality, of course, the kinds of causation involved in both levels are always involved in political transformation, and it may not be productive to try to sort out which level has greater causal importance.

Ideologies and organizations are clearly intertwined. Organizations have purposive agendas; and one important mechanism for furthering their agendas is to influence the content and nature of prominent expressions of social worldviews. So funneling cash into right-leaning think tanks, enhancing the visibility and credibility of their spokesmen, and turning up the volume on extreme right-wing media outlets are all understandable strategies of ideological conflict. (Naomi Oreskes' and Eric Conway's important book Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming documents these strategies in the case of climate science; link.) But likewise, the currency of a bundle of ideological beliefs and values in a part of the population is a huge boost for the ability of an organization to finance itself, draw followers, and exercise influence.

So we can look at the rise of large social movements, including those based on hate and suspicion, from two complementary perspectives. We can consider the micro-level processes through which beliefs and activism spread through a population, and we can look at the higher-level factors of ideology and organization within which these political processes unfold. In reality, of course, the kinds of causation involved in both levels are always involved in political transformation, and it may not be productive to try to sort out which level has greater causal importance.

Friday, June 10, 2016

Making change happen

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

10:50 AM

There are many large social ills that we would collectively like to change. We would like to see an end to debilitating poverty; we would like to end the systematic disparities by race that exist in our society, in health, education, or income; we would like to see gun violence rates drop to levels found in other advanced countries; we would like to see a dramatic reduction in the smoking rate among young people. And we would like to see crucial public institutions like public schools function at a superlative level. How feasible is it to deliberately bring about change in these kinds of social realities? In particular, how much real leverage do change agents like mayors, governors, presidents, or corporate or foundation leaders have in bringing about these kinds of social progress? How about community activists and community-based organizations?

There are a few considerations that make it clear that reforms leading to large social change in a short time will be very difficult. The example of the War on Poverty discussed in the prior post is instructive (link). On the one hand this case demonstrates that determined political leadership can succeed in focusing large amounts of resources in deliberate policy packages aimed at solving big problems. On the other hand detailed review of the WoP shows that there are very hard questions about causation and policy effectiveness that are still hard to answer (Bailey and Danzinger, Legacies of the War on Poverty).

One reason for the difficulty of large interventions is that these social problems are "wicked problems" with densely interconnected sets of causes (link). John Kolko defines a wicked problem in these terms:

A wicked problem is a social or cultural problem that is difficult or impossible to solve for as many as four reasons: incomplete or contradictory knowledge, the number of people and opinions involved, the large economic burden, and the interconnected nature of these problems with other problems. Poverty is linked with education, nutrition with poverty, the economy with nutrition, and so on. These problems are typically offloaded to policy makers, or are written off as being too cumbersome to handle en masse. Yet these are the problems�poverty, sustainability, equality, and health and wellness�that plague our cities and our world and that touch each and every one of us. (link)The interconnected nature of these difficult social problems means that attacking one component of causes may inadvertently worsen another source of causation, making the original problem worse. This is one of the discoveries that emerged from the effort to invoke systems engineering and the expertise of the aerospace industry to address urban problems in the 1960s (Hughes and Hughes, Systems, Experts, and Computers: The Systems Approach in Management and Engineering, World War II and After).

Another source of difficulty in addressing large system social problems is the question of scale of the resources that any actor can bring to bear on a large social problem. Private organizations have limited resources, and governments are increasingly constrained in their use of public resources by anti-tax activism. Cities are chronically caught in fiscal crises that make long-term investments difficult or impossible. And Federal funding since the Reagan revolution has been subject to intense opposition by the right. Finally, it is almost always true that a given strategy of change produces winners and losers, and groups that stand to lose something of value through the exercise of a strategy have many means of resisting change -- through lobbying, through strategic use of the legal system, or through exit. It is often difficult to build a sustainable consensus of political support for a large strategy of transformation or to overcome self-interested opposition.

That said, change sometimes occurs, and it sometimes occurs as a result of determined and intelligent strategic work by one or more agents of change. Recent examples in Michigan include the "Grand Bargain" that resolved the Detroit bankruptcy; the substantial progress achieved by a new Detroit mayor on delivering city services; substantial economic recovery in the state of Michigan since the 2007 recession; and the success of the Affordable Care Act in bringing health coverage to tens of millions of previously uninsured Americans (including about 600,000 in Michigan alone).

So it is possible for important social change to occur through deliberate political and policy action. But notice the limits of each of the examples cited here. Each involves taking a fairly simple policy step and maintaining political support for carrying out that policy. Too many uninsured people? Design a way of expanding an existing program to make health insurance more available to poor and middle-income individuals and families. The politics were horrendously difficult for President Obama, but the mechanics were clear. Need to save pensions and a world-class art collection from the Detroit bankruptcy process? Do some fundraising on a very large scale to allow an acceptable resolution of the bankruptcy process that preserves these two core things. Again, the task of maintaining the coalition was enormously difficult, but the mechanics of the strategy were not very different from other kinds of fundraising efforts in support of collective goods.

Let's think about the problem from another angle. What needs to happen in order for large social change to occur? Here are a couple of categories of change: change of law and policy; change of widespread social values; change of widespread patterns of behavior and disposition (smoking, racism, education); change of distribution of outcomes across a diverse population (health, income, residence). These examples fall in a couple of large types: setting legal and bureaucratic structures (Civil Rights Act, Department of Housing and Urban Development), influencing behavior, and changing values and attitudes.

What are the levers of change for these different kinds of social reality? Consider first structures. Law, policy, and taxation are the result of political and legislative competition. So legislative agendas by politicians and advocacy by interest groups and lobbyists are the main variables in determining the success or failure of a given initiative. The War on Poverty is a good example; the Johnson administration sought to create a number of large funding programs affecting housing, education, and employment, and it succeeded in part in many of these initiatives because the Democrats controlled both houses of Congress. (Though recall the frustration expressed by President Johnson at Congressional underfunding of many of these initiatives, expressed in his message to Congress on cities; link.)

Governments can address problems like these from two broad avenues: anti-discrimination law and policy initiatives aimed at addressing the obstacles that stand in the way of economic opportunity. Civil rights legislation supporting voting rights and legislation aimed at eliminating discrimination represent the first lever. Using federal funds to improve urban transportation and housing illustrates the latter.

Using the power of the state to raise revenues for initiatives like these through taxation is crucial. The War on Poverty was not chiefly an effort at persuasion; it was a determined political effort to direct Federal resources at enormously important national problems.

Policy change is hard. But achieving behavioral, attitudinal, and cultural change is even harder, it would appear. There is a lot of uncertainty about the causal mechanisms that might drive culture and behavioral change on a large scale. Further, there is often deep conflict about the content of culture change: what is a favorable attitude change for one group is anathema for another. Both considerations point in the direction of privileging non-governmental organization and community-based organization strategies over governmental strategies. Government and law must pay attention to behavior, not attitudes. So the burden of striving to change attitudes and values seems to belong to private initiatives within civil society. So the non-profit Michigan-based social service organization ACCESS can create and promote the "Take on Hate" program for young people as a way of addressing anti/Muslim bigotry, whereas the Department of Education probably couldn't. The national movement aimed at changing the public's attitudes towards same-sex marriage is a good example of a broad coalition of non-governmental organizations and groups successfully bringing about substantial change in public attitudes over a relatively short time.

In order to achieve lasting solutions to major social problems, it seems that all the avenues mentioned here will be needed: legislative action providing for real equality of opportunity and access for poor people to society's positions and advantages; public investment in factors like improved transportation, education, internet access, and green spaces; and private and collaborative efforts at generating public support for change of policy and behavior on a short list of particularly important social problems.

Thursday, June 9, 2016

LBJ's commitment to cities

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

8:56 AM

In the United States we have been in the desert for decades when it comes to big, transformative policy reforms aimed at addressing our most serious social issues. But the 1960s marked a decade of vigorous national effort to address some of our most serious and difficult social problems -- racial discrimination, war, poverty, education, and the quality of life of poor children and the elderly. It is worth thinking back to the large ambitions and strategies that were adopted between 1960 and 1968, the election of Richard Nixon.

A very interesting place to begin is Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty, and especially his 1968 Special Message to the Congress on Urban Problems: "The Crisis of the Cities." (link). Martha Bailey and Sheldon Danziger's volume Legacies of the War on Poverty provides a rigorous specialist assessment of the achievements (and shortcomings) of the war on poverty. Johnson's message is powerful in each of its rhetorical components -- aspiration, diagnosis, and policy recommendations.

A very interesting place to begin is Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty, and especially his 1968 Special Message to the Congress on Urban Problems: "The Crisis of the Cities." (link). Martha Bailey and Sheldon Danziger's volume Legacies of the War on Poverty provides a rigorous specialist assessment of the achievements (and shortcomings) of the war on poverty. Johnson's message is powerful in each of its rhetorical components -- aspiration, diagnosis, and policy recommendations.

The document paints a high-level picture of the way in which cities had developed in the United States in the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century. And the narrative for the 20th century builds to a sense of deepening urban crisis.

We see the results dramatically in the great urban centers where millions live amid decaying buildingswith streets clogged with traffic; with air and water polluted by the soot and waste of industry which finds it much less expensive to move outside the city than to modernize within it; with crime rates rising so rapidly each year that more and more miles of city streets become unsafe after dark; with increasingly inadequate public services and a smaller and smaller tax base from which to raise the funds to improve them.The document identifies a host of key problems in American cities: inner-city youth with limited education and opportunity; violent crime; deep penetration of prejudice and discrimination in the normal workings of social life; poor public health levels; and disaffection among inner city citizens, both young and old.

The city will not be transformed until the lives of the least among its dwellers are changed as well. Until men whose days are empty and despairing can see better days ahead, until they can stand proud and know their children's lives will be better than their own -- until that day comes, the city will not truly be rebuilt.

The document emphasizes both material and psychological factors -- poor housing and "empty and despairing" lives. Johnson links the crisis of cities with the goals and achievements of the fundamental Civil Rights legislation of the recent past.

Johnson's urban policy recommendations focus on several key city-centered crises: poor housing, inadequate public mass transit, extensive urban blight, high unemployment for young people, and institutions supporting lending and insurance for urban homeowners. The document also recommends increased support for urban-centered social-science research.

What is most noteworthy is the overall ambition of Johnson's agenda: the goal of devoting substantial organizational effort at the federal level (through the establishment of new agencies like HUD) and billions of dollars to implement effective solutions for these awesomely difficult and important social problems. It is striking that we have not had national leaders since LBJ with the courage and vision to set such an ambitious agenda for progressive social change. The persistent problems of poverty, race, and educational failure will be amenable to nothing less.

There is one other aspect of Johnson's message that is of interest here -- the sociology of knowledge implications of the document. This is a good example of a place where an STS approach would be helpful. There is probably an existing literature on the policy expertise that underlay Johnson's reasoning in this document, but I haven't been able to identify the person who drafted this message on Johnson's behalf. But there is obviously a high level of expertise and judgment implicit in this document -- and this certainly doesn't derive from the president himself. What is the paradigm of urban theory and policy that drives the reasoning of the document and the associated policy proposals? And what are the blindspots associated with that historically situated research framework? Causes, outcomes, and levers of change for urban decline are all identified. Are these still credible as empirical theories of urban realities?

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)