Showing posts with label fascism. Show all posts

Saturday, August 20, 2016

The rise of Austrofascism

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

2:29 PM

Several recent posts have commented on the rise of a nationalistic, nativist politics in numerous contemporary democracies around the world. The implications of this political process are deeply challenging to the values of liberal democracy. We need to try to understand these developments. (Peter Merkl's research on European right-wing extremism is very helpful here; Right-wing Extremism in the Twenty-first Century.)

One plausible approach to trying to understand the dynamics of this turn to the far right is to consider relevantly similar historical examples. A very interesting study on the history of Austria's right-wing extremism between the wars was published recently by Janek Wasserman, Black Vienna: The Radical Right in the Red City, 1918-1938.

Wasserman emphasizes the importance of ideas and culture within the rise of Austrofascism, and he makes use of Gramsci's concept of hegemony as a way of understanding the link between philosophy and politics. The pro-fascist right held a dominant role within major Viennese cultural and educational institutions. Here is how Wasserman describes the content of ultra-conservative philosophy and ideology in inter-war Vienna:

The ideas represented within its institutions ran a broad spectrum, yet its discourse centered on radical anti-Semitism, German nationalism, v�lkisch authoritarianism, anti-Enlightenment (and antimodernist) thinking, and corporatism. The potential for collaboration between Catholic conservatives and German nationalists has only in recent years begun to attract scholarly attention. (6)This climate was highly inhospitable towards ideas and values from progressive thinkers. Wasserman describes the intellectual and cultural climate of Vienna in these terms:

At the turn of the century, Austria was one of the most culturally conservative nations in Europe. The advocacy of avant-garde scientific theories therefore put the First Vienna Circle� and its intellectual forbears� under pressure. Ultimately, it left them in marginal positions until several years after the Great War. In the wake of the Wahrmund affair, discussed in chapter 1, intellectuals advocating secularist, rationalist, or liberal views faced a hostile academic landscape. Ernst Mach, for example, was an intellectual outsider at the University of Vienna from 1895 until his death in 1916. Always supportive of socialist causes, he left a portion of his estate to the Social Democrats in his last will and testament. His theories of sensationalism and radical empiricism were challenged on all sides, most notably by his successor Ludwig Boltzmann. His students, among them David Josef Bach and Friedrich Adler, either had to leave the country to find appointments or give up academics altogether. Unable to find positions in Vienna, Frank moved to Prague and Neurath to Heidelberg. Hahn did not receive a position until after the war. The First Vienna Circle disbanded because of a lack of opportunity at home. (110-111)Philosophy played an important role in the politics of inter-war Vienna, on both the right and the left. Othmar Spann was a highly influential conservative thinker who openly defended the values of National Socialism. On the left were Enlightenment-inspired philosophers who were proponents for reason and science. The pioneering analytic philosopher and guiding light of the Vienna Circle was Moritz Schlick. In 1934 Schlick was required to report to the Viennese police to demonstrate that the Vienna Circle was not a political organization (Black Vienna, 106). Schlick responded with three letters intended to demonstrate factually that the Circle was "absolutely unpolitical". He defended a conception of value-free science, and maintained that the debates considered by the Vienna Circle were entirely within the scope of value-free science. But, as Wasserman points out, the doctrines of positivism and modern scientific rationality that were at the core of Vienna Circle philosophy were themselves politically contentious in the conservative intellectual climate of inter-war Vienna. It is also true that some members of the circle were in fact active progressive thinkers and actors. The most overtly political member of the Vienna Circle was Otto Neurath, who had been imprisoned for his participation in the Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1918.

Intellectual influence depends on the ability of an intellectual movement to gain positions in universities and other cultural institutions. The effort to win positions of influence in Austrian universities and other leading cultural institutions was strongly weighted towards the conservatives and nationalists:

A comparison of placement success with the Vienna Circle of logical empiricists is telling. Spann managed to place four students into full professorships in Austria during the interwar period; Moritz Schlick did not manage to place a single one. Likewise, the psychologists Karl and Charlotte B�hler could not place anyone in German or Austrian universities. Although members of Schlick�s and B�hler�s respective circles attracted international recognition for their work in philosophy and science, they could not find institutional security in interwar Austria. The converse was true for the members of Spannkreis: they dominated the Austrian intellectual landscape yet enjoyed little international success. (91)

The assassination of Moritz Schlick was a single tragic moment in this large historical canvas. Schlick was shot to death in the main building of the university by a right-wing student, Johann Nelb�ck, in 1936. The background of the assassination appears to have involved politics as well as personal grievances, according to a document titled "Philosophie der Untat", drafted by Professor Eckehart K�hler in 1968 and made publicly available in the 2000s through Reddit (link). K�hler's document is well worth reading. It was drafted in 1968 and printed by the Union of Socialist Students of Austria for distribution at a philosophy of science conference in Vienna; but the student organization then got cold feet about the claims made and dumped 2000 copies into the Danube River. The document was rediscovered in the 1990s. According to K�hler, Nelb�ck was influenced by reactionary Vienna philosopher Leo Gabriel. It is apparent that the scientific philosophy of the Vienna Circle was at odds with the conservative thought that dominated Vienna; in fact, after his pardon by the Nazi government after the Anschluss, Nelb�ck proposed to create an alternative to positivism that he named "negativism". It is ironic that the violence against Schlick had to do with the philosophy of positivism rather than the political program of socialism.

The University of Vienna had a shameful history during the Nazi period. Following the Anschluss the university expelled more than 2,700 faculty and students, most of whom were Jewish, according to Professor Katharina Kniefacz's short history of these issues in the university (link). "Anti-Semitic tendencies culminated in the complete and systematic expulsion of Jewish teachers and students from the University of Vienna after Austria's 'Anschluss' to the National Socialist German Reich in 1938" (6). Few were invited to return, and public contrition for these expulsions only began to occur in the 1990s. According to Kniefacz, anti-semitism within the university persisted for decades after the end of Nazi rule. And two rectors of the university who served without objection during the Nazi period are memorialized in the Main Building of the University (10).

This history is still of great relevance in Austria today. The Austrian far right came within a handful of votes of winning the presidency in May 2016, based on a virulent anti-immigrant platform. And the country's high court has now invalidated that election, preparing the ground for a second election later this year. It is a very good question to wonder how widespread attitudes of racism, nativism, and anti-semitism are in the Austrian population today -- the very climate of racism and intolerance mentioned in the Schlick memorial above.

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

Liberalism and hate-based extremism

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

6:17 PM

How should a democratic society handle the increasingly virulent challenges presented by hate groups, anti-government extremists, and organizations that encourage violence and discrimination against others in society? Should extremist groups have unlimited rights to advocate for their ideologies of hatred and antagonism against other groups within a democracy?

Erik Bleich has written extensively on the subject of racist speech and the law. Recent books include The Freedom to Be Racist?: How the United States and Europe Struggle to Preserve Freedom and Combat Racism and Race Politics in Britain and France: Ideas and Policymaking since the 1960s. Bleich correctly notes that these issues are broader than the freedom-of-speech framework in which they are often placed; so he examines law and policy in multiple countries on freedom of speech, freedom of association, and freedom of opinion-as-motive. In each of these areas he finds important differences across European countries and the United States with respect to legislation concerning racist expressions. In particular, liberal democracies like Great Britain, France, and Germany have created legislation to prohibit various kinds of hate-based speech and action. Here is his summary of the status of European legislation:

European restrictions on racist expression have proceeded gradually but consistently since World War II. A few provisions were established in the immediate postwar era, but most countries� key laws were enacted in the 1960s and 1970s. The statutes have been tinkered with, updated, and expanded in the ensuing decades to the point where virtually all European liberal democracies now have robust hate speech laws on their books. These laws are highly symbolic of a commitment to curb racism. But they are also more than just symbols. As measured by prosecutions and convictions, levels of enforcement vary significantly across Europe, but most countries have deployed their laws against a variety of racist speech and have recently enforced stiffer penalties for repeat offenders. (kl 960)In the United States it is unconstitutional under the First Amendment of the Constitution to prohibit "hate speech" or to ban hate-based organizations. So racist and homophobic organizations are accorded all but unlimited rights of association and expression, no matter how odious and harmful the content and effects of their views. As Bleich points out, other liberal democracies have a very different legal framework for regulating hate-based extremism by individuals and organizations (France, Germany, Sweden, Canada).

Here is the First Amendment of the US Constitution:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.This is pure liberalism, according to which the state needs to remain entirely neutral about disagreements over values, and the only justification for legal prohibition of an activity is the harm the activity creates. There is a strong philosophical rationale for this position. John Stuart Mill maintains an ultra-strong and exceptionless view of freedom of expression in On Liberty. He argues that all ideas have an equal right to free expression, and that this position is most advantageous to society as a whole. Vigorous debate leads to the best possible set of beliefs. Here are a few passages from On Liberty:

The object of this Essay is to assert one very simple principle, as entitled to govern absolutely the dealings of society with the individual in the way of compulsion and control, whether the means used be physical force in the form of legal penalties, or the moral coercion of public opinion. That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. (13)

But the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error. (19)This line of reasoning leads to legal toleration in the United States of groups like the White Citizens Councils, Neo-Nazi parties, and the Westboro Baptist Church to conduct their associations, propaganda, and demonstrations to further their hateful objectives. And they and their activists sometimes go further and commit acts of terrible violence (Timothy McVeigh, the murder of Matthew Shepherd in Wyoming, and the murders of civil rights workers in Mississippi).

But as Mill acknowledges, a democratic society has a right and an obligation to protect its citizens from violence. This is the thrust of the "harm" principle in Mill's philosophy of political authority. Is right-wing extremism (RWE) really just another political platform, equally legitimate within the public sphere of debate in a democratic society? Or do these organizations represent a credible threat to personal safety and civil peace?

Certainly most of the disagreements between liberals and conservatives fall in Millian category -- how much a society should spend on social welfare programs, what its immigration policies ought to be, the legal status of single-sex marriage. The disagreements among the parties are intense, but the debates and positions on both sides are legitimate. Mill is right about this range of policy disagreements. The political process and the sphere of public debate should resolve these disagreements.

But RWE goes beyond this level of disagreement about policy and legislation. RWE represents a set of values and calls to action that are inconsistent with the fundamentals of a democratic society. And they are strongly and essentially related to violence. RWE activists call for violence against hated groups, they call for armed resistance to the state (e.g. the Bundy's), and they actively work to inculcate hatred against specific groups (Muslims, Jews, African Americans, gays and lesbians, ...). These groups are anti-constitutional and contemptuous of the common core of civility upon which a democratic society depends.

There are two fundamental arguments against hate-based speech and associations that seem to justify exceptions to the general liberal principle of toleration of offensive speech. One is an argument linking hate to violence. There is ample historical evidence that hateful organizations do in fact stimulate violence by their followers (Birmingham bombing, lynchings and killings of civil rights workers, the assassination of Yitzak Rabin). So our collective interest in protecting all citizens against violence provides a moral basis for limiting incendiary hate speech and organization.

The second kind of argument concerns hate itself, and the insidious effects that hateful ideologies have on individuals, groups, and the polity. EU reports make an effort to capture the essential nature and harms of hate (link). Hate incites mistrust, disrespect, discrimination, and violence against members of other groups. The social effects of hate are toxic and serious. Do these effects suffice to justify limiting hate speech?

This is a difficult argument to make within the context of US jurisprudence. The realm of law involves coercion, and it is agreed that the threshold for interfering with liberty is a high one. It is also agreed that legal justifications and definitions need to be clear and specific. How do we define hate? Is it explained in terms of well-known existing hatreds -- racism, anti-semitism, islamophobia, homophobia, ...? Or should it be defined in terms of its effects -- inculcating disrespect and hostility towards members of another group? Can there be new hatreds in a society -- antagonisms against groups that were previously accepted without issue? Are there legitimate "hatreds" that do not lead to violence and exclusion? Or is there an inherent connection between hatred and overt antagonism? And what about expressions like those of Charlie Hebdo -- satire, humor, caricature? Is there a zone of artistic expression that should be exempt from anti-hate laws?

Here is Bleich's considered view on the balance between liberty and racism. Like Mill, he focuses on the balance between the value of liberty and the harm created by racist speech and action.

To telegraph the argument here, my perspective focuses on the level of harm inflicted on individuals, victim groups, and societies. For individuals and victim groups, the harm has to be measurable, specific, and intense. For societies, racism that fosters violence or that drives wedges between groups justifies limiting freedom of expression, association, and opinion-as-motive. (kl 247)Further:

Racist expressions, associations, or actions that drive a wedge between segments of society or that provoke an extremely hostile response have little redeeming social value. Their harm to other core liberal democratic values such as social cohesion and public order simply outweighs any potential benefits to be gained by protecting them. At the same time, if the statements or organizations are designed to contribute to public debate about state policies, they have to be rigorously protected, even if they may have potentially damaging side effects. (kl 3403)And here are the closing words of advice offered in the book:

How much freedom should we grant to racists? The ultimate answer is this: look at history, pay attention to context and effects, work out your principles, convince your friends, lobby your representatives, and walk away with a balance of values that you can live with. (kl 3551)The issue to this point has been whether the state can legitimately prohibit hate speech and organization. But other avenues for fighting hateful ideas fall within the realm of civil society itself. We can do exactly as Mill recommended: offer our own critiques and alternatives to hatred and racism, and strive to win the battle of public opinion. Empirically considered, this is not an entirely encouraging avenue, because a century of experience demonstrates that hate-based propaganda almost always finds a small but virulent audience. So it is not entirely clear that this remedy is sufficient to solve the problem.

These are all difficult questions. But the rise and virulence of hate-based groups across the world makes it urgent for democracies to confront the problem in a just way, respecting equality and liberty of citizens while stamping out hate. And there are pressing practical questions we have to try to answer: do the non-coercive strategies available to the associations of civil society have the capacity to securely contain the harmful spread of hate-based organizations and ideologies? And, on the other hand, do the more restrictive legal codes against racism and hate-based organizations actually work in France or Germany? Or does the continuing advance of extremist groups there suggest that legal prohibition had little effect on RWE as a political movement? And if both questions turn out unfavorably, does liberalism face the possibility of defeat by the organizations of hatred and racism?

Monday, August 1, 2016

Ethnography of the far right

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

7:33 PM

Can we understand the dynamics of far-right extremism without understanding far-right extremists? Probably not; it seems clear we need to have a much more "micro" understanding of the actors than we currently have if we are to understand these movements so antithetical to the values of liberal democracy. And yet there isn't much of a literature on this subject.

An important exception is a 2007 special issue of the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, curated by Kathleen Blee (link). This volume brings together several ethnographic studies of extremist groups, and it makes for very interesting reading. Kathleen Blee is a pioneer in this field and is the author of Inside Organized Racism: Women in the Hate Movement (2002). She writes in Inside Organized Racism:

Intense, activist racism typically does not arise on its own; it is learned in racist groups. These groups promote ideas radically different from the racist attitudes held by many whites. They teach a complex and contradictory mix of hatred for enemies, belief in conspiracies, and allegiance to an imaginary unified race of "Aryans." (3)

One of Blee's key contributions has been to highlight the increasingly important and independent role played by women in right-wing extremist movements in the United States and Europe.

The JCE issue includes valuable studies of right-wing extremist groups in India, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia. And each of the essays is well worth reading, including especially Blee's good introduction. Here is the table of contents:Key questions concerning the mechanisms of mobilization arise in almost all the essays. What are the mechanisms through which new adherents are recruited? What psychological and emotional mechanisms are in play that keep loyalists involved in the movement? Contributors to this volume find a highly heterogeneous set of circumstances leading to extremist activism. Blee argues that an internalist approach is needed to allow us to have a more nuanced understanding of the social and personal dynamics of extremist movements. What she means by externalist here is the idea that there are societal forces and "risk factors" that contribute to the emergence of hate and racism within a population, and that these factors can be studied in a general way. An internalist approach, by contrast, aims at discovering the motives and causes of extremist engagement through study of the actors themselves, within specific social circumstances.

But it is problematic to use data garnered in externalist studies to draw conclusions about micromobilization since it is not possible to infer the motivations of activists from the external conditions in which the group emerged. Because people are drawn to far-right movements for a variety of reasons that have little connection to political ideology (Blee 2002)�including a search for community, affirmation of masculinity, and personal loyalties� what motivates someone to join an anti-immigrant group, for example, might�or might not�be animus toward immigrants. (120)Based on interviews, participant-observation, and life-history methods, contributors find a mix of factors leading to the choice of extremist involvement: adolescent hyper-masculinity, a desire to belong, a history of bullying and abuse, as well as social exposure to adult hate activists. But this work is more difficult than many other kinds of ethnographic research because of the secrecy, suspiciousness, and danger associated with these kinds of activism:

Close-up or �internalist� studies of far-right movements can provide a better understanding of the workings of far-right groups and the beliefs and motivations of their activists and supporters, but such studies are rare because data from interviews with members, observations of group activities, and internal documents are difficult to obtain.... Few scholars want to invest the considerable time or to establish the rapport necessary for close-up studies of those they regard as inexplicable and repugnant, in addition to dangerous and difficult. Yet, as the articles in this volume demonstrate, internalist studies of the far right can reveal otherwise obscured and important features of extreme rightist political mobilization. (121-122)A few snippets will give some flavor of the volume. Here is Michael Kimmel's description of some of the young men and boys attracted to the neo-Nazi movement in Sweden:

Insecure and lonely at twelve years old, Edward started hanging out with skinheads because he �moved to a new town, knew nobody, and needed friends.� Equally lonely and utterly alienated from his distant father, Pelle met an older skinhead who took him under his wing and became a sort of mentor. Pelle was a �street hooligan� hanging out in street gangs, brawling and drinking with other gangs. �My group actually looked down on the neo-Nazis,� he says, because �they weren�t real fighters.� �All the guys had an insecure role as a man,� says Robert. �They were all asking �who am I?�� ...

Already feeling marginalized and often targeted, the boys and men described themselves as �searchers� or �seekers,� kids looking for a group with which to identify and where they would feel they belonged. �When you enter puberty, it�s like you have to choose a branch,� said one ex-Nazi. �You have to choose between being a Nazi, anti-Nazi, punk or hip- hopper�in today�s society, you just can�t choose to be neutral� (cited in Wahlstrom 2001, 13-14). ...

For others, it was a sense of alienation from family and especially the desire to rebel against their fathers. �Grown-ups often forget an important component of Swedish racism, the emotional conviction,� says Jonas Hallen (2000). �If you have been beaten, threatened, and stolen from, you won�t listen to facts and numbers.�(209-210)Here is Meera Sehgal's description of far-right Hindu nationalist training camps for young girls in India:

The overall atmosphere of this camp and the Samiti�s camps in general was rigid and authoritarian, with a strong emphasis on discipline. ... A number of girls fell ill with diarrhea, exhaustion, and heat stroke. Every day at least five to ten girls could be seen crying, wanting to go home. They pleaded with their city�s local Samiti leaders, camp instructors, and organizers to be allowed to call their parents, but were not allowed to do so. ... Neither students nor instructors were allowed to get sufficient rest or decent food.And here is Fabian Virchow's description of the emotional power of music and spectacle at a neo-Nazi rally in Germany:

The training was at a frenetic pace in physically trying conditions. Participants were kept awake and physically and mentally engaged from dawn to late night. Approximately four hours a day were devoted to physical training; five hours to ideological indoctrination through lectures, group discussions, and rote memorization; and two hours to indoctrination through cultural programming like songs, stories, plays, jokes, and skits. Many girls and women were consequently soon physically exhausted, and yet were forced to continue. The systematic deprivation of adequate rest and food may have been a deliberate ploy of the camp organizers to reduce the chances of dissent since time, energy, initiative, and planning are needed to develop a collective sense of grievance.

Indoctrination, which was the Samiti�s first priority, ranged from classroom lectures and small and large group discussions led by different instructors, to nightly cultural programs where skits, storytelling, songs, and chants were taught by the instructors and seasoned activists, based on the lives of various �Hindu� women, both mythical and historical. (170)

Festivals are excellent opportunities for far-right groups to spread the word about their successes to like-minded activists and sympathizers, since visitors come from as far away as Italy to see White Power music bands. In the festival mentioned above, a folk-dance act in the afternoon attracted only some hundred spectators, but evening performances by the U.S. band Youngland drew a large crowd that pushed to the front of the stage, leaving only limited space for burly skinheads indulging in pogo dancing. The music created a ritual closeness and attachment among the audience, shaping the emotions and aggression of the like-minded crowd, initially in a playful way, but one that switched into brutality a few moments later.

The aggression of White Power music is evident in the messages of its songs, which are either confessing, demonstrating self-assertion against what is perceived as totally hostile surroundings, or requesting action (Meyer 1995). Using Heavy Metal or Oi Punk as its musical basis, White Power music not only attracts those who see themselves as part of the same political movement as the musicians, but also serves as one of the most important tools for recruiting new adherents to the politics of the far right (Dornbusch and Raabe 2002).

Since the festival I visited takes place only once a year, and because performances of White Power bands are organized clandestinely in most cases and are often disrupted by the police, the far-right movement needs additional events to shape and sustain its collective identity. As the far right and the NPD and neo-Nazi groupuscules in particular regard themselves as a �movement of action,� it is no surprise that rallies play an important role in this effort. (151)Each of these essays is based on first-hand observation and interaction, and they give some insight into the psychological forces playing on the participants as well as the mobilizational strategies used by the leaders of these kinds of movements. The articles published here offer a good cross-section of the ways in which ethnographic methods can be brought to bear on the phenomenon of extremist right-wing activism. And because the studies are drawn from five quite different national contexts (Sweden, Germany, Netherlands, India, France), it is intriguing to see some of the same mechanisms and dynamics in play in creating and sustaining an extremist movement. The importance of performance and music in eliciting loyal participation from young adherents comes up in the articles about Germany, Sweden, and India. Likewise the importance of the emotional needs of boys as they approach manhood, and the hyper-masculine themes of violence and brutality in the neo-Nazi organizations that appeal to them, recurs in several of the essays.

Along with KA Kreasap, Kathleen Blee is also the author of a 2010 review article on right-wing extremist movements in Annual Reviews of Sociology (link). These are the kinds of hate-based organizations and activists tracked by the Southern Poverty Law Center (link), and that seem to be more visible than ever before during the current presidential campaign. The essay pays attention to the question of the motivations and "risk factors" that lead people to join right-wing movements. Blee and Kreasap argue that the motivations and circumstances of mobilization into right-wing organizations are substantially more heterogeneous than a simple story leading from racist attitudes to racist mobilization would suggest. They argue that antecedent racist ideology is indeed a factor, but that music, culture, social media, and continent social networks also play significant causal roles.

Friday, July 29, 2016

Survey research on right-wing extremism in Europe

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

2:41 PM

European research and policy organizations have devoted a fair amount of attention to the rise of extremist movements and intolerance in European countries in the past ten years. Attention has been directed towards both aspects of the problem that have been mentioned in earlier posts -- rising public attitudes of intolerance, and the mobilization and spread of hate-based right-wing organizations. (The topic has also received a great deal of attention in the press -- for example, in the Guardian (link), the New York Times (link), and Spiegel (link).)

One useful report is Intolerance, Prejudice and Discrimination: A European Report (link), authored by Andreas Zick, Beate Kupper, and Andreas Hovermann (Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2011). The study is based on survey research in eight countries (Germany, Britain, France, Netherlands, Italy, Portugal, Poland, and Hungary). Particularly interesting are the results on anti-semitism, anti-muslimism, and homophobia (56 ff.). Here are the opening paragraphs of the authors' foreword:

Intolerance threatens the social cohesion of plural and democratic societies. It reflects the extent to which we respect or reject social, ethnic, cultural and religious minorities. It marks out those who are �strange�, �other� or �out- siders�, who are not equal, less worthy. The most visible expression of intolerance and discrimination is prejudice. Indicators of intolerance such as prejudice, anti-democratic attitudes and the prevalence of discrimination consequently represent sensitive measures of social cohesion.And here are a few of their central findings, based on survey research in these eight countries:

Investigating intolerance, prejudice and discrimination is an important process of self-reflection for society and crucial to the protection of groups and minorities. We should also remember that intolerance towards one group is usually associated with negativity towards others. The European Union acknowledged this when it declared 1997 the European Year against Racism. In the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam the European Union called for joint efforts to combat prejudice and discrimination experienced by groups and individuals on the basis of their ethnic features, cultural background, religion, gender, sexual orientation, age or disability. (11)

Group-focused enmity is widespread in Europe. It is weakest in the Netherlands, and strongest in Poland and Hungary. With respect to anti-immigrant attitudes, anti-Muslim attitudes and racism there are only minor differences between the countries, while differences in the extent of anti-Semitism, sexism and homophobia are much more marked.

About half of all European respondents believe there are too many immi- grants in their country. Between 17 percent in the Netherlands and more than 70 percent in Poland believe that Jews seek to benefit from their forebears� suffering during the Nazi era. About one third of respondents believe there is a natural hierarchy of ethnicity. Half or more condemn Islam as �a religion of intolerance�. A majority in Europe also subscribe to sexist attitudes rooted in traditional gender roles and demand that: �Women should take their role as wives and mothers more seriously.� With a figure of about one third, Dutch respondents are least likely to affirm sexist attitudes. The proportion opposing equal rights for homosexuals ranges between 17 percent in the Netherlands and 88 percent in Poland; they believe it is not good �to allow marriages between two men or two women�. (13)These researchers find three underlying "ideological orientations" associated with these patterns of intolerance and discrimination: authoritarianism, "social dominance orientation", and the rejection of diversity. And the factors that work against intolerance include "trust in others, the ability to forge firm friendships, contact with immigrants, and above all a positive basic attitude towards diversity" (14).

The topic of the incidence of intolerance in European countries is also the subject of research in the Eurobarometer project. Here are two Eurobarometer reports from 2008 and 2012 that attempt to measure changes in levels of discrimination and prejudice (Discrimination in the European Union, 2008; link; 2012; link).

Also from the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung is the report Is Europe on the "Right" Path?: Right-wing extremism and right-wing populism in Europe (link). This report provides country studies of the radical right in Germany, France, Britain, Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Bulgaria, Poland, Hungary, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. Here is how Britta Schellenberg undertakes to synthesize these wide-ranging findings:

Taken as a whole, the contributions in the present volume clearly illustrate the common features and differences within the radical right in Europe. Analyses of the current phenomenon of the various radical-right movements and a differentiated analysis of their origins are fundamental for considering counter-strategies. Obviously, there is no single, generally valid strategy that guarantees an optimal way of combating the radical right. In fact, strategies can be successful only if they match up to the specific political and social context and if the maximum possible number of players from politics, the legal system, the media, educational institutions and civil society are agreed upon them.Each country study is detailed and interesting. The France study focuses on the Front National and Jean-Marie Le Pen's success (and later Marine Le Pen's success) since the 1984 European election in gaining visible support and electoral success with 10% to 15% of the vote (84). The Mouvement pour la France (MPF) and its leader Philippe de Villiers also receive attention in the report. And the resurgence of skinheads and direct action neo-fascists like the "violence-prone street brawlers of the Groupe Union Defense" are discussed (89-90).

However, we can identify general requirements for strategies against right-wing extremism and xenophobia that form a framework broad enough to allow a European perspective. For concrete work in a particular place, this framework must be filled out with individual measures and activities specific to the situation and location. But for now, we shall now proceed to take a bird�s eye view and answer the basic questions as to what preconditions have to be created for maximum success in combating radical-right-wing attacks, parties and attitudes. (309)

The essay develops a handful of strategies for combatting right-wing movements:

- A comprehensive approach: Identifying and naming problems and strategically combating the radical right

- Political involvement: Confront, don�t cooperate

- Determining the focus: Protection against discrimination, and diversity and equality

- Allowing civil society to develop, and strengthening civic commitment

- Education for democracy and human rights

- The EU is being degraded into an enforcer of austerity measures across the continent. It is essential to restore the idea of the EU as a regional network of states that stand together in solidarity in order to promote mutual wellbeing, good living standards, tolerant societies, and democratic values that are shared by all.

- Furthermore it is vital to explain the local benefits of EU membership to ordinary people with a clear and understandable message.

- There need to be more efficient and accessible training and exchange programmes in order to decrease the distance between EU institutions and citizens.

- Diversity must be increased and a greater inclusiveness within EU institutions is required, with mechanisms to enable a much more accurate representation of the European population in EU institutions.

- Progressives should be strident in defending greater global and European integration against the often empty criticisms of right-wing populists and extremists.

- We recommend that different stakeholders collaborate with each other in a knowledge exchange in order to provide public officials with EU-wide training.

- Establishing quotas for those who are elected as candidates, by increasing leadership in minority groups, and via private-public partnerships to help promote equality in business as well as the public sector.

- Hate speech has to be monitored in the European Parliament by an independent body and the existing sanctions regarding hate speech need to be reviewed.

- Social media should be used in this effort to confront the advocacy of hatred and that a dialogue should be promoted between internet providers and social media companies, examining among others the possibility of creating a new platform for non-governmental organizations and the civil society. (5-6)

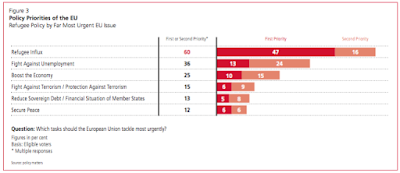

Here is a summary table based on results from all eight countries ranking the relative weight of EU priorities for EU citizens. Solving the refugee crisis dwarfs concern about other issues, though unemployment comes in as a substantial second.

Given Brexit, it is interesting to see the relative levels of dissatisfaction with EU membership in other countries as well. An average of 34% of respondents found that "disadvantages exceed advantages" in EU membership for their country, with the Czech Republic at 44% on this question and Spain at only 22%.

These are interesting survey results describing the growth of right-wing extremism in Europe. But these studies are limited in their explanatory reach. They are largely descriptive; they give a basis for assessing the dimensions of the problem in terms of population attitudes and right-wing extremist organizations. But there is little by the way of sociological analysis of the mechanisms through which these extremist attitudes and processes of activism proliferate and grow. In an upcoming post I will review some recent work on the ethnography of right-wing movements that will allow a somewhat deeper understanding of the dynamics of these movements.

Tuesday, July 19, 2016

Ideologies and organizations as causes of political extremism

Posted by

Amazing People,

on

4:31 AM

In a recent post I addressed the issue of the rise of mass intolerance and hate from the point of view of the public -- the processes through which sizable numbers of members of society come to be more intolerant in their attitudes and behaviors. This involves looking at the problem as being analogous to epidemiology -- the contagion through a population of the social psychology of hate and intolerance.

But this is only a part of the story. Right-wing political movements are fueled by ideologies and organizations, and when they come to power their success is at least partially attributable to these higher-level social factors. A movement can't succeed without gaining grassroots followers, to be sure. But it may be that the authoritarian and racist politics of a movement derive more from the higher-level factors of ideology and organization than the retail racism and social psychology of the populace.

This is the heart of the approach taken by Fritz Stern in The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in the Rise of the Germanic Ideology , where he gives a careful and detailed accounting of the philosophies and mental frameworks that underlay the progress of reactionary and racist parties in Germany (link). It is also the approach taken by Janek Wasserman in Black Vienna: The Radical Right in the Red City, 1918-1938, where the ideas of conservative religious dogmas, anti-semitism, and a hatred of modern secularism fueled the rise of Austrofascism. Wasserman gives little attention to the street-level politics of the struggles and mobilizations of left and right in Austria (unlike Arthur Koestler's gritty accounts of the mobilizations and street fighting of communists and fascists in Berlin; link).

, where he gives a careful and detailed accounting of the philosophies and mental frameworks that underlay the progress of reactionary and racist parties in Germany (link). It is also the approach taken by Janek Wasserman in Black Vienna: The Radical Right in the Red City, 1918-1938, where the ideas of conservative religious dogmas, anti-semitism, and a hatred of modern secularism fueled the rise of Austrofascism. Wasserman gives little attention to the street-level politics of the struggles and mobilizations of left and right in Austria (unlike Arthur Koestler's gritty accounts of the mobilizations and street fighting of communists and fascists in Berlin; link).

If we look at the problem from this point of view, then the rise of right-wing extremist movements needs to be analyzed in terms of the ideologies that lead them and the organizations through which they attempt to bring about their political ends. In the United States the ideology of the right has a number of leading values: religious fundamentalism, nativism, anti-government and anti-tax rhetoric, free market fundamentalism, suspicion, homophobia, and cultural conservativism. And these threads have been woven together into powerful and motivating narratives of American history and the political choices the country faces for tens of millions of Americans.

In this light the writings of Richard Hofstadter, discussed in an earlier post, are quite important. Hofstadter traces the specifics of a fairly distinctive conservative ideology in the United States, a worldview of society and politics that has persisted in the organs of public expression -- newspapers, activists, professors, clergy -- over a very long time. And these tropes in turn find expression in the activism and mobilization of extremist groups like the armed groups who took over the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge last winter. These ideological strands become currents of extremist values around which individual entrepreneurs organize their appeals to potential followers. (Many of these themes are finding expression on the convention stage in Cleveland this week.)

It is a very interesting question to consider how mass consciousness in a population maintains a "folk" political philosophy over generations. How have American nativism and mistrust of government been sustained in the populace since 1900? Why does anti-semitism persist so strongly in some European countries where the Holocaust left almost no Jewish residents at all? What are the mechanisms of transmission and reproduction that make this possible? To what extent is this an organic process of popular transmission, and to what extent is it the result of ongoing ideological struggles? It is clear that ideologies have institutional embodiments. And it is an important task for political sociology to map out the ways these institutions work. Obviously newspapers, media, religious centers, and universities play key roles in the transmission of political frameworks to new generations of citizens; and the influence of family traditions and daily discussions of current events play a crucial role in the transmission of values and frameworks as well.

The organizations of the right include a range of configurations of groups in civil society -- right-wing political parties, religious organizations, anti-government groups, and cause-based organizations (anti-gay marriage, pro-gun groups, business advocacy groups, conservative student organizations). The hate groups tracked by the SPLC are the extreme fringe of this world. These kinds of organizations do their best to frame political choices and antagonisms around their core ideological tropes, and they do everything possible to stir up the emotions and angers of their followers and potential followers around these values.

Ideologies and organizations are clearly intertwined. Organizations have purposive agendas; and one important mechanism for furthering their agendas is to influence the content and nature of prominent expressions of social worldviews. So funneling cash into right-leaning think tanks, enhancing the visibility and credibility of their spokesmen, and turning up the volume on extreme right-wing media outlets are all understandable strategies of ideological conflict. (Naomi Oreskes' and Eric Conway's important book Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming documents these strategies in the case of climate science; link.) But likewise, the currency of a bundle of ideological beliefs and values in a part of the population is a huge boost for the ability of an organization to finance itself, draw followers, and exercise influence.

So we can look at the rise of large social movements, including those based on hate and suspicion, from two complementary perspectives. We can consider the micro-level processes through which beliefs and activism spread through a population, and we can look at the higher-level factors of ideology and organization within which these political processes unfold. In reality, of course, the kinds of causation involved in both levels are always involved in political transformation, and it may not be productive to try to sort out which level has greater causal importance.

Ideologies and organizations are clearly intertwined. Organizations have purposive agendas; and one important mechanism for furthering their agendas is to influence the content and nature of prominent expressions of social worldviews. So funneling cash into right-leaning think tanks, enhancing the visibility and credibility of their spokesmen, and turning up the volume on extreme right-wing media outlets are all understandable strategies of ideological conflict. (Naomi Oreskes' and Eric Conway's important book Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming documents these strategies in the case of climate science; link.) But likewise, the currency of a bundle of ideological beliefs and values in a part of the population is a huge boost for the ability of an organization to finance itself, draw followers, and exercise influence.

So we can look at the rise of large social movements, including those based on hate and suspicion, from two complementary perspectives. We can consider the micro-level processes through which beliefs and activism spread through a population, and we can look at the higher-level factors of ideology and organization within which these political processes unfold. In reality, of course, the kinds of causation involved in both levels are always involved in political transformation, and it may not be productive to try to sort out which level has greater causal importance.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)